A couple of days ago, I had the pleasure of chatting with Jeff Bezos before and after he gave an excellent talk to about 500 of our alumni. Jeff made a number of interesting (and humorous) observations, speaking on topics ranging from why Amazon experiments actively to how we've become a society of information "snackers" to his basis for spousal choice ("someone who can get me out of a third-world prison").

What made me think the most during the few minutes we chatted was his (seemingly simple) framework for making difficult decisions. Innovative companies like Amazon often have to make big decisions with little or no data. In making these choices, Jeff says that his choice is governed by "what would be better for the customer?". His point was that in the long-run, the interests of one's customers are perfectly aligned with the interests of one's shareholders. (This is clearly not the case when one has to manage short-term earnings.) He cited cases ranging from launching Amazon Prime to allowing customer reviews (both positive and negative) to remain on the site as examples where this framework paid off in the long run.

This observation (which seems to make more sense the more one thinks about it, although "perfectly" aligned might be a slight simplification) is an interesting one when applied to data ownership. Because it implies that in making data collection and retention choices, the smartest companies might be the ones who formulate policies that are aligned most clearly with the welfare of their customers. This is a lot simpler than thinking about expected future value and liability. I'm not yet convinced, but there's something interesting here.

I still don't have a comfortable feel for why they've entered the cloud computing business, but that's a subject for a different post.

Friday, April 18, 2008

Monday, April 7, 2008

Kansas, Memphis, data: value and liability

I ended up watching the Kansas-Memphis game. The first college basketball game I've watched this year. Nevertheless, I made many predictions. Most of which were wrong.

The one prediction I was most confident about was when Kansas made the 3-point shot in the last seconds, tying the game. At that point, it was absolutely clear to me that they would win the game. I had no data, no context, no history, but it didn't matter. All I had to do was look at the faces of the teams, and it was so clear who would perform better in the next 5 minutes. I didn't need historical performance data of any kind.

Companies have so much customer data these days. These data seems valuable, and worth storing, even though their value isn't immediately apparent. But I wonder if we're forgetting that data in isolation might not be marginally that valuable any more, and further, that firms need to understand how to associate a data trail with a conversation and a person before making a business decision. And if they don't, while they might anticipate value from mining the data in the future, perhaps they shouldn't be keeping the data, because it could end up being a liability to them. As Professor Vasant Dhar and I have discussed and written about in the past, firms may well need to rethink their "data valuation" models and strategies.

Just one dimension of a much larger discussion about how firms should manage their customer data.

The one prediction I was most confident about was when Kansas made the 3-point shot in the last seconds, tying the game. At that point, it was absolutely clear to me that they would win the game. I had no data, no context, no history, but it didn't matter. All I had to do was look at the faces of the teams, and it was so clear who would perform better in the next 5 minutes. I didn't need historical performance data of any kind.

Companies have so much customer data these days. These data seems valuable, and worth storing, even though their value isn't immediately apparent. But I wonder if we're forgetting that data in isolation might not be marginally that valuable any more, and further, that firms need to understand how to associate a data trail with a conversation and a person before making a business decision. And if they don't, while they might anticipate value from mining the data in the future, perhaps they shouldn't be keeping the data, because it could end up being a liability to them. As Professor Vasant Dhar and I have discussed and written about in the past, firms may well need to rethink their "data valuation" models and strategies.

Just one dimension of a much larger discussion about how firms should manage their customer data.

Labels:

analytics,

data governance,

data mining,

privacy

Tuesday, March 25, 2008

The social role/responsibility of business

My dean Tom Cooley is a firm believer in the role of business as an agent of social change and progress. In case you are wondering why this is related to digital strategy, check out the wonderful story of ITC's eChoupal that we discussed in my MBA class today.

I'm torn about two issues on this subject:

(1) Where should a business draw the line between maximizing familiar "shareholder value" metrics and facilitating broader social transformation and progress? I respect the writings of both Milton Friedman and Ed Freeman, but their views diverge pretty radically on this front. Or do they?

(2) Is it sensible to allow a corporation to own physical and technological infrastructure essential to a nation's commerce? This is clearly a more important question for developing countries. However, before you conclude that its only relevant to them: the Internet took off after it was freed from the shackles of DoD ownership. As a consequence, an essential and integral piece of today's U.S. commercial infrastructure is entirely owned by a handful of telecom companies. Leading to, for instance, debates about net neutrality.

Anyway, food for thought. Look forward to your feedback.

I'm torn about two issues on this subject:

(1) Where should a business draw the line between maximizing familiar "shareholder value" metrics and facilitating broader social transformation and progress? I respect the writings of both Milton Friedman and Ed Freeman, but their views diverge pretty radically on this front. Or do they?

(2) Is it sensible to allow a corporation to own physical and technological infrastructure essential to a nation's commerce? This is clearly a more important question for developing countries. However, before you conclude that its only relevant to them: the Internet took off after it was freed from the shackles of DoD ownership. As a consequence, an essential and integral piece of today's U.S. commercial infrastructure is entirely owned by a handful of telecom companies. Leading to, for instance, debates about net neutrality.

Anyway, food for thought. Look forward to your feedback.

Saturday, March 15, 2008

The Amazon platform paradox

My MBA class and I took a look at Amazon's 2007 numbers last week.

Sure, the 40% revenue growth is impressive. What's more notable, however, is that Amazon's operating income is growing even faster (on the order of about 60% ), despite them ramping up IT spending to north of $800M. This suggests a couple of things:

(1) Amazon's high-margin "platform" services are probably generating an increasing fraction of their revenue.

(2) Spending over $800M on technology and less than half of that on marketing suggests that Amazon is clearly committed to growing the more pure-IT-centric parts of their business model. In a sense, these are substitutes, because growing the platform plays a key role in attracting and retaining customers.

(Remember the November 2006 BusinessWeek article that suggested Wall Street was worried about Amazon not focusing on its core retailing business? Here's how Amazon's stock has performed since then, relative to a large traditional retailer:)

It looks like Bezos' risky bet is paying off. But here's the paradox. First, Amazon built the most enduring aspects of its platform -- scalable ecommerce fulfilment and inventory management -- by raiding WalMart's experts. Makes one wonder why WalMart, with its legendary supply-chain expertise, couldn't do this themselves. Second, having created capabilities that set it apart from the ecommerce pack, Amazon was bold enough to turn itself "inside out", and, rather than leveraging this core competency, offer its computing, process and human expertise up to anyone competitor who wanted to pay for it. This is almost like WalMart deciding to rent out its procurement and supply chain to its competitor's in the '90s, rather than using it as the source of proprietary advantage that led to their dominance. And, strikingly, this platform business model is working. Maybe there's a parallel with American Airlines and the Sabre system from a few decades ago.

Sure, the 40% revenue growth is impressive. What's more notable, however, is that Amazon's operating income is growing even faster (on the order of about 60% ), despite them ramping up IT spending to north of $800M. This suggests a couple of things:

(1) Amazon's high-margin "platform" services are probably generating an increasing fraction of their revenue.

(2) Spending over $800M on technology and less than half of that on marketing suggests that Amazon is clearly committed to growing the more pure-IT-centric parts of their business model. In a sense, these are substitutes, because growing the platform plays a key role in attracting and retaining customers.

(Remember the November 2006 BusinessWeek article that suggested Wall Street was worried about Amazon not focusing on its core retailing business? Here's how Amazon's stock has performed since then, relative to a large traditional retailer:)

It looks like Bezos' risky bet is paying off. But here's the paradox. First, Amazon built the most enduring aspects of its platform -- scalable ecommerce fulfilment and inventory management -- by raiding WalMart's experts. Makes one wonder why WalMart, with its legendary supply-chain expertise, couldn't do this themselves. Second, having created capabilities that set it apart from the ecommerce pack, Amazon was bold enough to turn itself "inside out", and, rather than leveraging this core competency, offer its computing, process and human expertise up to anyone competitor who wanted to pay for it. This is almost like WalMart deciding to rent out its procurement and supply chain to its competitor's in the '90s, rather than using it as the source of proprietary advantage that led to their dominance. And, strikingly, this platform business model is working. Maybe there's a parallel with American Airlines and the Sabre system from a few decades ago.

So here's to Amazon's continued growth. Though it might be wise to steer clear of cloud computing as a business line. Do they really want Google and Microsoft as direct competitors?

Sunday, March 9, 2008

The open iPhone: why Jobs is still guarding the gate

Last Thursday, Apple took a bold step, opening the iPhone and releasing the SDK (software development kit) that facilitates developing iPhone applications. Jobs has now moved away from the "control" we've seen impede Apple's technological leadership over the last 20 years, but is doing so in a measured and strategically sensible manner. Here's why.

The iPhone will be an incredibly tempting platform to build on, and the SDK will attract a lot of talent. However, Apple still controls what you can install, and if you pay, takes 30% of the revenue. If its free, Apple decides. So a lot of what is developed isn't going to generate revenue, or even be available to you. As a software developer, you're therefore going to try a lot harder. Especially since you might want your slice of the dedicated $100M iFund

And as Apple generates platform revenue and value, it simultaneously makes sure the user experience can be controlled. Thereby not making the mistake Facebook has, where there's now a lot of clutter that is damaging what used to be a clean user experience. This is an especially important consideration for Apple: they owe a large part of the success of their recent generations of devices and software to superior and simpler user-device interfaces.

Sure, this revenue cut implies higher prices for paid applications. Which aligns really well with the current (high-income) iPhone user base. Perhaps this will be revisited as the platform grows, the iPhone's technology becomes more stable, and the device becomes mass-market (if this ever happens). Let's wait and see.

Labels:

Apple,

iFund,

iPhone,

network effects,

platforms

Wednesday, February 27, 2008

The promise and perils of DRM-free music

It has been a fascinating few months for digital music. We've seen Apple become the second largest music retailer in the US, and we've also seen all the major labels sign up to sell music digitally, on Amazon, as MP3's, and DRM-free.

I'm worried about the latter development. Yes, the labels see the need to thwart Apple's growing channel power (which stems from their control of the "rendering interface"). If iTunes becomes the de-facto channel for buying digital content, it seems like only a matter of time before Apple starts to get a larger fraction of the revenue (right now, seems like the labels get at least ten times what Apple gets in operating income when you buy an iTunes song). This kind of channel control becomes even more critical as video and books become digital.

But if the music labels give up rights and distribution, they need a new business model. I see why they'd want to stymie Apple's growing channel power, but I'm really not sure this "DRM-free" choice is a good strategic move. I always felt that the pure digitization of music represented an opportunity for the labels to manage digital rights. As one of my student groups pointed out on Monday, 90% of music sold legally is still DRM-free -- all music sold on a CD.

So embracing DRM seems like a good way to sustain control in a digital future. I guess the labels didn't understand that they should have taken control of the DRM and rendering standards as well. They could have if their executives were tech savvy, or if the people who understood technology were the decision makers. But they were not. Giving these standards to Apple resembles the mistake IBM made by giving the operating system to Microsoft back in the early 80's, when PC's were new. Which has led to Microsoft capturing a vast majority of the revenues from PC sales over the decades -- $20 billion in operating income this year alone from Windows and Office.

Stripping DRM is perilous at this point. Owning the DRM standard and the rendering interface are what will define market power and channel c0ntrol in the digital economy. Apple has this to lose -- but they need to share if they want to leverage it over the next decade.

I'm worried about the latter development. Yes, the labels see the need to thwart Apple's growing channel power (which stems from their control of the "rendering interface"). If iTunes becomes the de-facto channel for buying digital content, it seems like only a matter of time before Apple starts to get a larger fraction of the revenue (right now, seems like the labels get at least ten times what Apple gets in operating income when you buy an iTunes song). This kind of channel control becomes even more critical as video and books become digital.

But if the music labels give up rights and distribution, they need a new business model. I see why they'd want to stymie Apple's growing channel power, but I'm really not sure this "DRM-free" choice is a good strategic move. I always felt that the pure digitization of music represented an opportunity for the labels to manage digital rights. As one of my student groups pointed out on Monday, 90% of music sold legally is still DRM-free -- all music sold on a CD.

So embracing DRM seems like a good way to sustain control in a digital future. I guess the labels didn't understand that they should have taken control of the DRM and rendering standards as well. They could have if their executives were tech savvy, or if the people who understood technology were the decision makers. But they were not. Giving these standards to Apple resembles the mistake IBM made by giving the operating system to Microsoft back in the early 80's, when PC's were new. Which has led to Microsoft capturing a vast majority of the revenues from PC sales over the decades -- $20 billion in operating income this year alone from Windows and Office.

Stripping DRM is perilous at this point. Owning the DRM standard and the rendering interface are what will define market power and channel c0ntrol in the digital economy. Apple has this to lose -- but they need to share if they want to leverage it over the next decade.

Labels:

digital music,

digital rights,

DRM,

itunes,

piracy

Monday, February 25, 2008

Micosoft and Yahoo: More than just a marriage of search

As Yahoo waits for a higher bid and Microsoft contemplates a proxy fight, it is useful to take advantage of this lull to think about why this merger makes sense. Everyone is thinking search, online advertising and the (losing?) battle with Google on these fronts, a strategic focus that has been sharpened further with the release of the text of a memo from Kevin Johnson a couple of days ago.

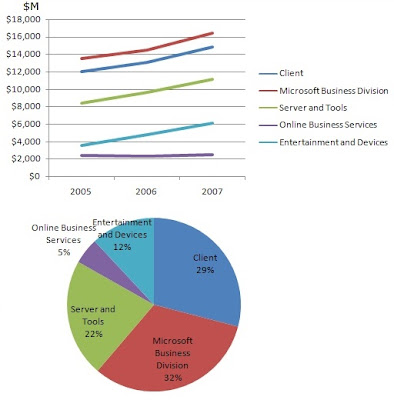

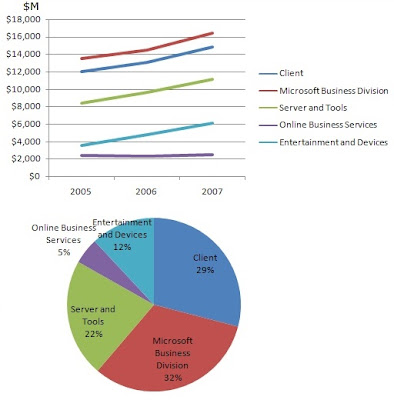

However, let's take a look at Microsoft's revenue breakdown (these numbers are from their most recent 10-K):

(read "Client" as "Windows" and "Business Division" as "Office")

(read "Client" as "Windows" and "Business Division" as "Office")

Sure, acquiring Yahoo could provide some momentum to the flat online services revenue curve. But this is still a pretty small slice of Microsoft's revenue pie. Even more telling is this breakdown of operating income, reminding us that a vast majority of the money Microsoft makes still comes from Office and Windows, and the rest from their enterprise business.

Alright. Now, I just finished Nick Carr's new book, The Big Switch, and I have to say that his arguments and technological sophistication have become admirably nuanced. This is a prescient read, one I'd recommend highly. So, let's say we're evolving towards a (distant) future in which a lot of basic IT infrastructure moves to massive computing grids. Microsoft has deep (although perhaps not all willing) customer loyalty in the PC world, and an impressive revenue stream (~$11B) from its server customers. If they're thinking ahead about a future in which this software is delivered over the Internet, wouldn't an ideal acquisition be a company with deep and diversified consumer relationships in the online world? And with technological sophistication and experience in delivering rich computing experiences over the Internet? Frankly, to me this sounds a lot like Yahoo! (which, Google aside, is one of the most Internet technology-savvy companies there is). Yahoo! is the online truly diversified portal left standing. It has an impressive range of properties that engage it's consumers. And notice the technological leadership it has taken with Hadoop.

Perhaps some of this is speculative thinking. And maybe the specter of a Google-owned online advertising world is part of the short-term motivation for the acquisition, and maybe online advertising will be the revenue engine for specific kinds of consumer software in the near future. But to me, this merger (which seems like it will happen) won't just be about search. It will determine who owns and controls future consumer and enterprise computing.

However, let's take a look at Microsoft's revenue breakdown (these numbers are from their most recent 10-K):

(read "Client" as "Windows" and "Business Division" as "Office")

(read "Client" as "Windows" and "Business Division" as "Office")Sure, acquiring Yahoo could provide some momentum to the flat online services revenue curve. But this is still a pretty small slice of Microsoft's revenue pie. Even more telling is this breakdown of operating income, reminding us that a vast majority of the money Microsoft makes still comes from Office and Windows, and the rest from their enterprise business.

Alright. Now, I just finished Nick Carr's new book, The Big Switch, and I have to say that his arguments and technological sophistication have become admirably nuanced. This is a prescient read, one I'd recommend highly. So, let's say we're evolving towards a (distant) future in which a lot of basic IT infrastructure moves to massive computing grids. Microsoft has deep (although perhaps not all willing) customer loyalty in the PC world, and an impressive revenue stream (~$11B) from its server customers. If they're thinking ahead about a future in which this software is delivered over the Internet, wouldn't an ideal acquisition be a company with deep and diversified consumer relationships in the online world? And with technological sophistication and experience in delivering rich computing experiences over the Internet? Frankly, to me this sounds a lot like Yahoo! (which, Google aside, is one of the most Internet technology-savvy companies there is). Yahoo! is the online truly diversified portal left standing. It has an impressive range of properties that engage it's consumers. And notice the technological leadership it has taken with Hadoop.

Perhaps some of this is speculative thinking. And maybe the specter of a Google-owned online advertising world is part of the short-term motivation for the acquisition, and maybe online advertising will be the revenue engine for specific kinds of consumer software in the near future. But to me, this merger (which seems like it will happen) won't just be about search. It will determine who owns and controls future consumer and enterprise computing.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)